Its meaning has undergone constant modifications throughout history

Its meaning has undergone constant modifications throughout history

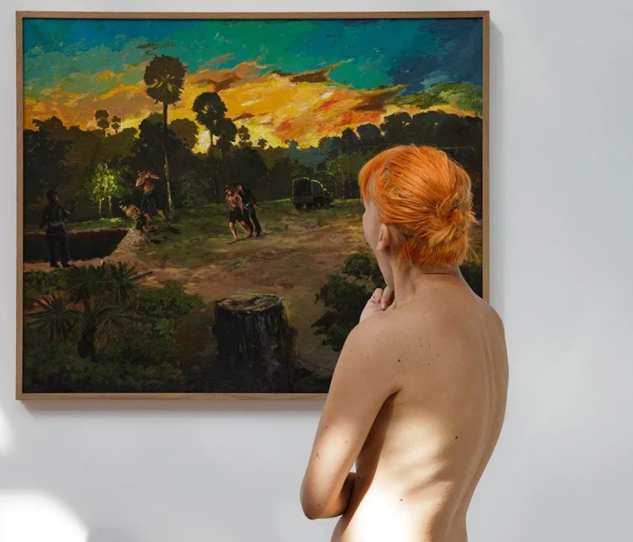

Art is a diverse range of human activity in the creation of visual, auditory, or performing artifacts (works of art), expressing the author’s imaginative, conceptual, or technical ideas, intended to be appreciated for their beauty or emotional power.

In general, these activities are connected with the production of works, artistic criticism, the study of their histories, and the aesthetic dissemination itself.

The three classical branches of art are:

- Painting,

- sculpture, and

- architecture.

Music, theater, film, dance and other performing arts, as well as literature and other media, such as interactive media, are included in a broader definition. Until the 17th century, art referred to any skill or domain, and was not differentiated from crafts or the sciences.

After the seventeenth century, where aesthetic considerations are paramount, the fine arts are separated and differentiated from generally acquired skills such as the decorative or applied arts.

Although the definition of what constitutes art is contested and has changed over time, general descriptions mention an idea of imaginative or technical skill, which stems from human agency and creation.

Its nature and related concepts, such as creativity and interpretation, are explored in a branch of philosophy known as aesthetics.

The origin of the term “Art”

Art (from the Latin term ars, meaning technique and/or skill) can be understood as the human activity related to the manifestations of aesthetic or communicative order, performed through a wide variety of languages, such as: architecture, drawing, sculpture, painting, writing, music, dance, theater, and cinema, in their various combinations.

The creative process is based on perception with the intention of expressing emotions and ideas, aiming for a unique and different meaning for each work.

More about the definition

The main problem in defining what art is is that this concept varies over time and according to various human cultures. We must keep in mind that the very definition of art is a variable cultural construction with no constant meaning.

What one group classifies as art will not necessarily fit another (because it is external to the environment where it was produced).

Pre-industrial societies, in general, do not have or even had a term to designate art. In a very simplified view, it is linked mainly to one or more of the following aspects:

- The manifestation of some special ability;

- the artificial creation of something by the human being;

- the triggering of some response in the human being, such as a

- sense of pleasure or beauty;

- the presentation of a certain order, pattern, or harmony;

- the transmission of a sense of novelty and uniqueness;

- the expression of the creator’s inner reality;

- the communication of something in the form of a special language

- the notion of value and importance;

- the excitement of imagination and fantasy;

- the induction or communication of a peak experience;

- things that are recognizably meaningful;

- things that give an answer to a given problem.

At the same time, even if a given activity is generally considered to be art, there is a lot of inconsistency and subjectivity in the application of the term. For example, it is customary among Westerners to call operatic singing an art; but singing carelessly while working is often not considered an artistic activity.

There may thus be a number of other parameters that cultures employ to separate what they do or do not consider to be art.

Even if one can, in theory, establish such general parameters valid consensually, the analysis of each case can be extraordinarily complex and inconsistent.

In a geographical context, if Western culture calls opera art, possibly an Oriental might consider that form of singing very strange.

In the historical perspective, often an object considered artistic in one era may not be so in another.

History of the concept

In the West, a general concept of art, that is, what things as different as, for example, a Renaissance madrigal, a Gothic cathedral, Homer’s poetry, medieval mystery plays, a Baroque altarpiece, would have in common, only began to take shape in the mid-18th century, although the word had already been in use for centuries to designate any special skill.

In classical antiquity, where one of the main foundations of Western civilization was formed, we had the first reflections on the subject, considering art as any activity that involved a special skill: whether it was building a boat; commanding an army; convincing an audience in a speech. In short, any activity that was based on defined rules and was subject to learning and technical development.

Banksy in ParisOn the other hand, poetry, for example, was not considered art, because it was considered the fruit of inspiration.

According to Plato, art represents an ability to do something intelligently through learning, and is a reflection of the human being’s creative potential.

Aristotle defined it as a disposition to produce things in a rational way.

Quintilian understood it as that which was based on method and order.

Cassiodorus, on the other hand, emphasized its productive and ordered aspect, pointing out three functions for it: to teach, to move, and to please or give pleasure.

This vision lasted through the Middle Ages, but in the Renaissance a change began: the productive trades and sciences were separated from the arts proper (poetry was included in the artistic domain for the first time).

The change was influenced by the Italian translation of Aristotle’s Poetics and by the progressive social rise of the artist, who sought a move away from artisans and craftsmen, and towards intellectuals, scientists and philosophers.

The artistic object came to be considered both a source of pleasure and a means of signaling social distinctions of power, wealth, and prestige, increasing patronage and collectionism.

Several treatises on the arts also began to appear, such as Leon Battista Alberti’s De pictura, De statua, and De re aedificatoria, and Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Commentaries. Ghiberti was the first to periodize the history of art, distinguishing it into classical, medieval and Renaissance.

Unlike Ghiberti, today, through archeology, history and geography, we can add to the periodization rock art: considered the oldest form of human artistic expression. Originated in the context of prehistory, the first records were produced around 40 thousand B.C., and may appear inside caves, grottos and on other rocky surfaces.

Renaissance and Mannerism

The Renaissance and Mannerism mark the beginning of modern history (late 15th century to the 18th century). In this context, the definition of beauty was relativized, favoring the artist’s personal vision and imagination, to the detriment of a unified, scientific concept. The fantastic and the grotesque were also valued.

Giordano Bruno introduced the concept of originality, because, for him, art has no rules, is unlearned and proceeds from inspiration.

Art in the 18th Century

In the 18th century, aesthetics began to be consolidated as a key element for the definition of art as we understand it today – despite the vagueness and inconsistencies of the concept.

Until then, all art in the West was inextricably linked to one or more defined functions, that is, it was an essentially utilitarian activity, serving to:

- The transmission of knowledge;

- structuring and decorating rituals and festivities;

- invocation / mediation of spiritual or magical powers;

- beautification of buildings, places and cities;

social distinction; - remembrance of history and preservation of traditions;

- moral, civic, religious and cultural education; and

- perpetuation of socially relevant values/ideologies

Scientism and Enlightenment

This paradigm shift was linked to the cultural transformations triggered by scientism and enlightenment. These currents of thought began to defend the thesis that art was not a science, it could not accurately describe reality, therefore, it could not be a suitable vehicle for true knowledge.

Not being a science, art passed into the sphere of emotion, sensoriality and feeling. The very origin of the word “aesthetics” derives from a Greek term meaning “sensation.”

In works by Jean-Baptiste Dubos, Friedrich von Schlegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Théophile Gautier and others, the concept of “art for art’s sake” was born, where it would have a purpose of its own, stripping it of all its former functionality, practical utility and associations with morality.

While this opened up a new and rich philosophical field, it generated important difficulties: the ability to understand ancient art in its own context was lost, and concepts based entirely on subjectivity were created, making it increasingly difficult to find objective common ground that could be applied to any kind of art, both to define it and to value or interpret its meaning.

The emergence of art museums

A testimony to this trend is the proliferation of museums in the 19th century, institutions where all categories of art are presented outside their original contexts.

Aestheticism was one of the basic theoretical elements for the emergence of Romanticism, which rejected the utilitarianism of art and gave a primary value to the creativity, intuition, freedom, and individual vision of the artist, elevating him to the status of demiurge and prophet, thus fostering the cult of genius.

On the other hand, aestheticism offered an alternative for describing aspects of the world and life that are beyond the reach of science and reason.

Charles Baudelaire was one of the first to analyze the relationship of art to progress and the industrial age, foreshadowing the notion that there is no absolute beauty, but that it is relative and changeable according to the times and the predispositions of each individual. Baudelaire believed that art had an eternal and unchanging component – its soul – and a circumstantial and transitory one – its body.

This dualism expressed nothing more than the duality inherent in man in his longing for the ideal and his confrontation with concrete reality.

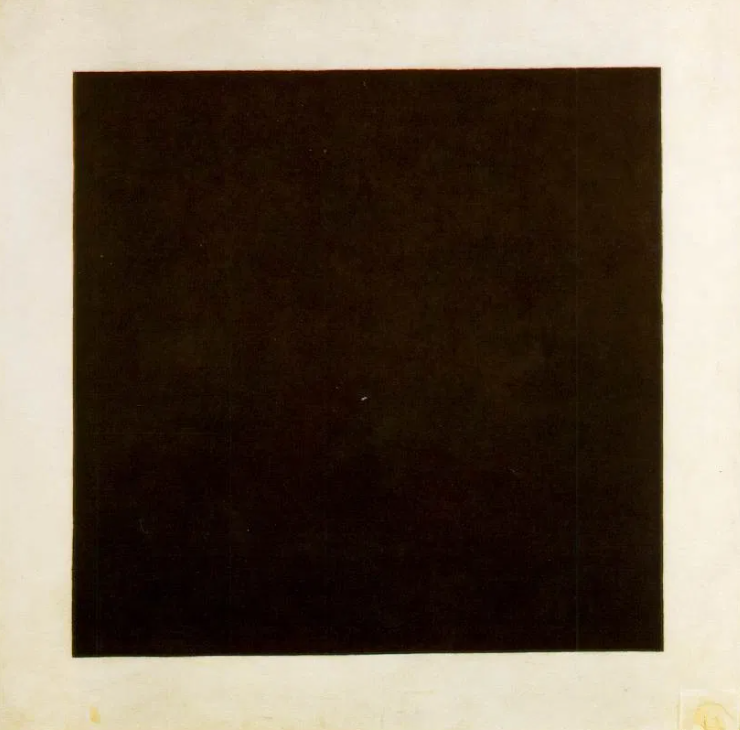

Despite the great influence of aestheticism, whose corollary would appear at the beginning of the 20th century in the form of abstractionism, an apotheosis of artistic individualism, there were currents that fought it, mainly because it is an art form (especially in the visual arts) that does not represent objects belonging to our exterior concrete reality. Instead, it uses formal relationships between colors, lines, and surfaces to compose the reality of the work, in a "non-representational" way.

Hippolyte Taine elaborated a theory that art has a sociological foundation, applying to it a determinism based on race, social context and time. He claimed, for aesthetics, a scientific character, with rational and empirical assumptions.

Jean-Marie Guyau presented an evolutionist perspective, stating that art is in life and evolves with it, and just as life is organized in societies, art should be a reflection of the society that produces it.

Sociological aesthetics had associations with left-wing political movements, especially utopian socialism, advocating, for art, the return to a social function, contributing to the development of societies and human brotherhood, as seen in the works of Henri de Saint-Simon, Lev Tolstoy, and Pierre Joseph Proudhon, among others.

John Ruskin and William Morris denounced the trivialization of art caused by aestheticism and industrial society, and advocated a return to the medieval corporate and artisanal system.

Psychology to explain art

Around the same time, art began to be studied from a psychological and semiotic point of view through the contribution of Sigmund Freud. He stated that art could be a form of representation of desires and sublimation of repressed irrational drives; that the artist was a narcissist, and that works could be analyzed in the same way as dreams, symbols and mental illnesses. This line was continued by his disciple Carl Jung, who introduced the concept of archetype in artistic analysis.

Another novelty was introduced by Wilhelm Dilthey, who considered art and life to be a unity; he noticed the importance of the public’s reaction in defining what an artistic object is, which established a kind of anarchy of taste, inaugurating cultural aesthetics. He also recognized that the times signaled a social change and a new interpretation of reality.

It was up to the artist to intensify his vision of the world in a coherent and meaningful work.

The art schools

Aestheticism, Romanticism, and all the social, economic, and cultural transformations in societies in the previous centuries laid the groundwork for new artistic meanings and representations in the early 20th century, making room for the formation of the European vanguards in the modernist period.

Innovative concepts were introduced by the Frankfurt School, especially Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno, studying the effects of industrialization, technology and mass culture on art.

Benjamin analyzed the loss of the aura of the artistic object in society, and Adorno reflected that art is not a mechanical reflection of the men who produce it, because it expresses what does not exist and indicates the possibility of transformation and transcendence.

The culmination of nature

Representative of pragmatism, John Dewey defined art as “the culmination of nature”, defending that the basis of aesthetics is sensorial experience.

Artistic activity would be a consequence of the natural activity of the human being, whose organizational form depends on the environmental conditions in which it develops. Thus, art would be the same as “expression”, where ends and means merge into a pleasant experience.

Ortega y Gasset, on the other hand, pointed out the elitist character and the dehumanization of avant-garde art, due to its hermeticism, the repudiation of the imitation of nature, and the loss of historical perspective. In the semiotic school, Luigi Pareyson elaborated a hermeneutic aesthetics, where art is the interpretation of truth.

For him, art is “formative,” that is, it expresses a way of doing that, at the same time, invents its own language and means.

Thus, art would not be the result of a predetermined project, but would simply find its result in the process of making. Pareyson influenced the so-called Turin School, which developed the ontological concept of art. Umberto Eco, its greatest exponent, stated that the work of art exists only in its interpretation, in the opening of multiple meanings that it can have for the spectator.

Starting in the second half of the 20th century, the subject became so complex, volatile, and subjective that many scholars have abandoned at all the idea that defining what art is is at all possible. We have, therefore, the beginning of contemporary art.

Again, historical transformations led to changes in artistic representations. After the war, artists showed themselves to be focused on the truths of the unconscious and interested in the reconstruction of society, changing customs and the needs of mass production. This revealed itself through the varied languages and through the constant experimentation with new techniques

As an example, some opinions about this new artistic context are cited: Morris Weitz stated that

“the very adventurous and expansive nature of art, its constant mutations and novelties, make it illogical for us to establish any set of definite properties.”

Robert Rosenblum said that “the idea of defining art today is so remote that I don’t think anyone would have the courage to do so,” and Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz said that “our century has come to the conclusion that achieving a comprehensive definition of what art is is not only extremely difficult, but impossible.

These views, however, have not prevented other critics from offering different opinions, believing that a conceptualization is possible.

George Dickie’s definition

Some of them bypassed the central problem of the definition itself, and established external parameters to define the artistic fact, resorting to institutional consecration, authority, the response of the public or people considered experts.

One example is George Dickie’s definition: “an artistic object is first of all an artifact, and second, it is a set of aspects that legitimize its proposal to deserve special attention from some person or persons acting on behalf of some social institution.

Sometimes one resorts to its location and cultural context, as in Thomas McEvilley’s statement that “what is in a museum is art… It seems pretty clear that nowadays more or less anything can be called art. The question is: has it been called art by the ‘art system’? In our century, that’s all it takes to define art.” In the same vein, Robert Hughes said that something is art “if it was created for the express purpose of being regarded as such and was placed in a context in which it is regarded as such.

ACCORDING TO THE DEFINITION OF THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA, ART IS THAT WHICH IS DELIBERATELY CREATED BY MAN AS AN EXPRESSION OF SKILL OR OF THE IMAGINATION.